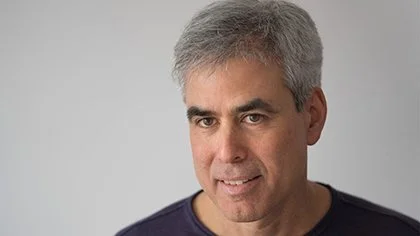

Research Comms Podcast: Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt on communicating with people across cultural divides

‘IQ and expertise make you very effective at generating reasons for why you or your side are right but they don’t necessarily make you more open-minded’. Social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, on why viewpoint diversity is so vital when it comes to engaging with new ideas.

That we’re living in highly polarised times won’t come as news to most people. Our natural propensity to tribalism has been let loose and public discourse has given way to people ranting and raving at anybody who doesn’t share their worldview. And all of this comes at a time when we need strong and healthy debates more than ever to to tackle the major challenges we face.

In this episode of Research Comms social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, author of the superb book ‘The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion’ talks about how we can break down barriers by talking to people’s ‘elephants’ and why the defence of viewpoint diversity in academic and research institutions is one of the most critical battles of our times, an argument laid out in his latest book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure

SUBSCRIBE ON

or wherever you listen to your podcasts…

The below is a short excerpt. For the full interview download the podcast.

The Righteous Mind does a fantastic job of undermining the idea that we are the rational minded creatures that we like to think of ourselves as. Why is that such an important thing to recognise?

I like to start with a an analysis of who we are as creatures and we evolved as tribal, ultra social emotional creatures. Somehow we're living above our design parameters but we are still tribal social emotional creatures and our moral judgment is bizarre if you think of it as an effort to find moral truth, it would be a very badly structured system for that, but if you see it as an aspect of human sociality that helps us to navigate webs of accountability and tribal loyalties then it all makes a lot more sense. So that's what The Righteous Mind is about and once you see that you become a lot more humble and less angry at the people on the other side because you recognise we're all animals with this very inconsistent and strategically oriented moral sense; we're all failures philosophically and once we recognise that we're on a firmer foundation for trying to figure out what should we actually do.

Have you listened to these other episodes of the Research Comms podcast?

One of the analogies you use in the book to describe the relationship between our intuitive selves and our rational mode of thinking is the rider and the elephant. How does that analogy work?

In the 1990s there was a kind of a revolution in social psychology as more and more psychologists recognised the power of automatic or intuitive thought, so in a way it's the return of Freud's unconscious, just stripped of all the sex and aggression and all the ornate plumbing that Freud had. But the idea is a sort of iceberg vision of the mind, in which only a small portion of mental processes are visible, which is our controlled or conscious reasoning, and almost everything else that happens is invisible to consciousness, so that's the way psychology was going in the 1990s and when I wrote my first book, The Happiness Hypothesis, which came out in 2006, I found that the greatest truth that all societies have discovered is that the mind is divided in two parts and that these sometimes conflict.

I thought a good metaphor for that would be something like a horse and rider, an animal and a person. A horse and rider is the obvious one but I wanted the horse to be much larger and much smarter, so I hit on the idea of an elephant. And the elephant doesn’t just represent emotion, it is all of our automatic processes, in other words the elephant is 99 percent of what goes on in our mind, and it's got its own intelligence, it can do many things much better than the rider; on the other hand the rider, being that little bit of conscious, that little bit of cognitive activity that we're aware of and that we can exert conscious control over, it does do some things that the elephant can't do. So maturity is a partnership; maturity is when the elephant and the rider each develop their own capabilities and work well together.

So talking to people’s ‘elephants’ is very important when it comes to communicating ideas. But how can we make sure we’re addressing their intuitive side, their elephants, rather than focusing exclusively on their reason, or their riders?

[this question came off the back of a discussion about how best to engage with climate change sceptics and the idea that Al Gore might not be the best choice to try to persuade those on the political right]

For a start effective persuasion means you have to address both the elephant and the rider. So, the person has to want to believe you and then have reasons to believe you. But if they don't want to believe you then they will not accept any reasons to believe you. So the two very important principles are ‘who is the messenger?’ and ‘have you acknowledged the the elephant's concerns?’

So if Al Gore is seen as a partisan Democrat, if he is seen as a scold or a hypocrite then he would not be an effective messenger. So that's the first thing ‘who is the messenger? And it's very powerful to have what Cass Sunstein the legal theorist, calls a ‘surprising validator’. To have Al Gore say “let's be worried about climate change” is not unexpected but to have the chief military officer or the Secretary of the of the Army or Navy say “you know climate change is a threat to our military and it will unleash challenges for the country” to have a military general or to have a CEO of a respected company, to have a religious leader who's not already on the left, these are much more effective spokespeople, people’s elephants will instantly take notice and be much more likely to listen.

What’s the second part of addressing the elephant in a persuasive argument?

You must acknowledge the person's concerns, so with climate change, at least in America the right early on latched onto the idea that really the Left just hates capitalism, industry, factories, cars and they're right, they're absolutely right! If you go to any climate march in America it's a mix of socialists, anti-capitalists, marijuana legalizing protestors, I mean it's the fringe left that has an agenda that is deeply disgusting to the right. And since climate change is part of that agenda why should they accept it?

I remember an episode of Glenn Beck, who was a very important voice in the Tea Party days, and Glenn Beck was saying “climate change is not about carbon dioxide and the environment it's about control” and you know, he's partly right. He's also partly wrong and I happen to think that climate change is one of the two or three greatest threats to humankind, but the point is that if you start by acknowledging their concerns that surprises them and it can break people out of their normal prejudices.

Research Comms is presented by Peter Barker, director of Orinoco Communications, a digital communications and content creation agency that specialises in helping to communicate research. Find out how we’ve helped research organisations like yours by taking a look at past projects…

LINKS

Jonathan’s Books

EXPLORE MORE FROM THE ORINOCO COMMS BLOG